In the morning bathed in the sun off the coast of Villefranche-Sur-Mer, Sagitta III Cutting through cobalt waters in the Mediterranean, past the calm marina and pine terrace in Côte D’Azur from France. A 40-foot-Dinasamai scientific ship after the frightening zooplankton with a hook-coated jaw to the lonely yellow buoy off the coast.

In the distance, the city of the resort was sparkling, a mirage from the villas of the pastel villas and church towers attached to the cliff. But up Sagitta IIIRomance ends on the rail. Lionel Guidi, a local scientist in Villefranche Oceanography Lab – known, with the right Frenchness, with his acronym Lov – peeking into the sea with practiced intensity.

He is here to lure plankton.

“There is life!” – Marine Technician Anthéa Bourhis

Around him, a veteran crew moved with precision, under the steel gaze of Captain Jean-Yves Carval. “Plankton is fragile,” warned the rough sailors, who spent nearly 50 years of carrier, trawls – and now, scientific boats. “If you are too fast, you make compote.”

The craft slowed when he reached a buoy, the sampling site where the guidi and his co -rays had collected marine data every day for decades. Under the deck, the head of the boat beard mechanic, Christophe Kieger, prepared a big winch. The 12,000 feet cable spreads it, sending a fine net of each pore is not wider than a salt-flanking in the inside. Slowly, sink up to 250 feet.

A few minutes later, the net appeared again, heavy with brownish Goo, agar.

“There is life!” Cries Anthéa Bourhis, a 28-year-old lab technician from Brittany, when he carefully moved its contents to a plastic bucket.

Indeed, the catch holds more than just sea water and mucus. This is the raw material of the planet’s past – and maybe its future.

Lionel Guidi, 44, a Plankton research scientist in Villefranche Oceanography Lab, known as LOV (part of the IMEV-Institut de la Mer de Villefranche, Sorbonne University-CNRS).

A worrying trend

Plankton forms the heartbeat of the ocean machine. This small organism absorbs carbon dioxide, releases oxygen, and supports all seafood nets. Without them, life as we know will not exist.

But what is plankton?

This is not a single creature, but A large number of sea wandeys, all bound by one trait: they cannot swim against the current. They floated with waves and vortex, driving an invisible flow that govern their lives. Some are not bigger than a speck of dust; Others, like jellyfish, can stretch more than one meter.

There are two main types. Those who use sunlight: phytoplankton – Photosynthetic microscopic sea plants such as green plants on land and, during geological time, have produced more than half of the oxygen that we breathe. And those who feed: Zooplankton -The small animals that graze on cousins like their plants, hunting each other, and they themselves become prey, supporting fish, whales, and seabirds.

In the Lab Oceanography Villefranche, scientists have tracked these creatures for decades. Their daily sampling, carried out only a few miles off the coast, has produced one of the longest continuous records of plankton in the world.

And that note now shows stress signs.

“At our observation location, the temperature measured by 10 meters below the surface has risen about 1.5 degrees Celsius over the past 50 years,” Lionel Guidi said UN News. “We have seen a general decline in primary phytoplankton production.”

The consequences have the potential for far reach. Phytoplankton forms the foundation of marine ecosystems, and the decrease in number may trigger cascading effects, interfere with zooplankton, fish stocks, and overall marine biodiversity. It can also weaken their ability to absorb carbon dioxide, interesting from the atmosphere and bring it into – what scientists are called ‘biological pumps’, one of the most vital natural climate regulators on earth.

Phronima, Zooplankton Sea Dalam, inspired the design of creatures in the 1979 film, “Alien.”

Small alien

Back to lov, with Sagitta III Now resting on his bed, Lionel Guidi gave a signal to the sample that day. “Everything starts with Plankton,” said the scientist, who, before landing at Villefranche, conducted marine research in Texas and Hawaii.

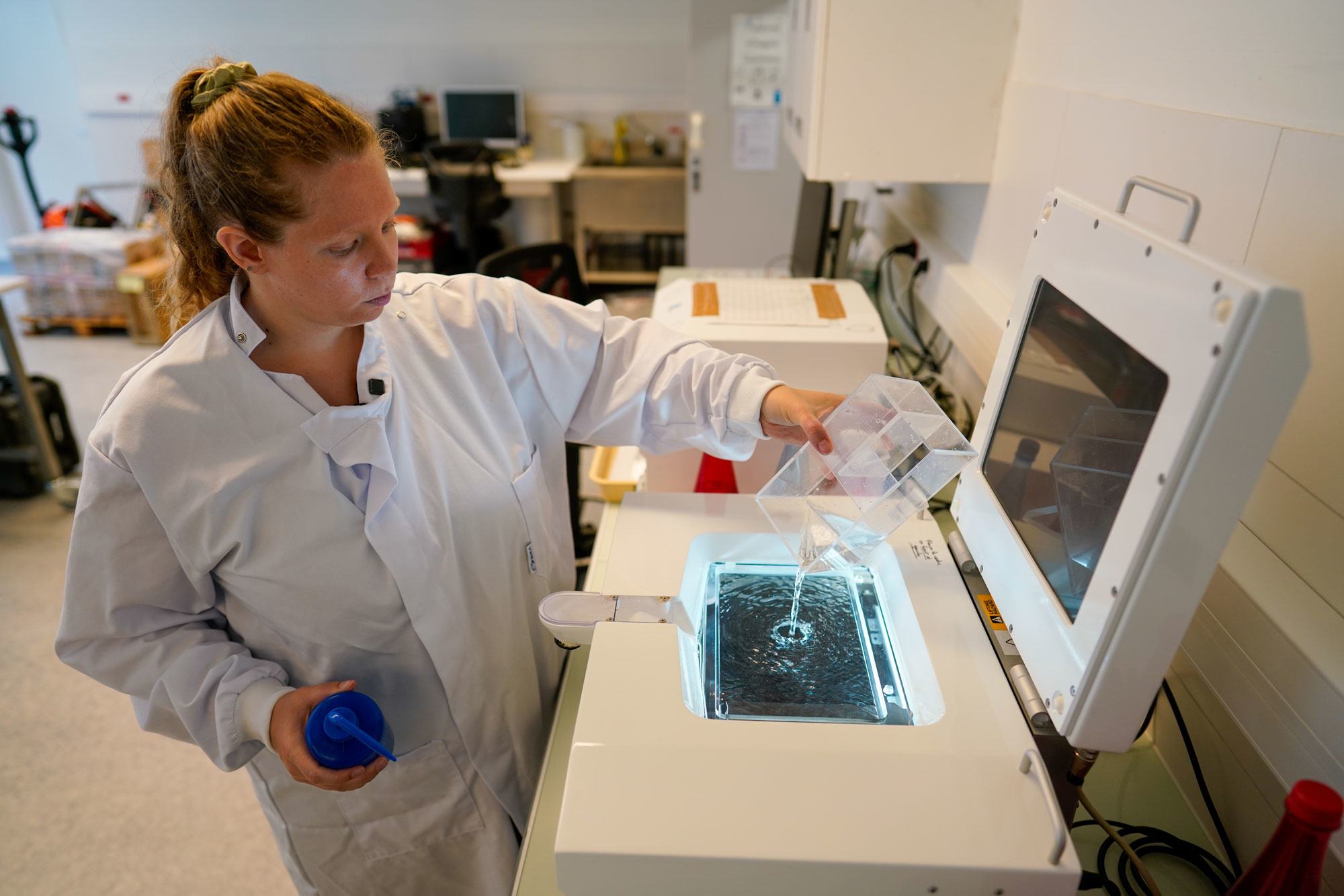

Meanwhile, Anthéa Bourhis, a young technician, was wearing a white lab coat and bent on the catch that morning. He fixed the sample in formaldehyde, a step that would store zooplankton but also killed them. “If they move, it disrupts the scan,” he explained.

After being silent, small animals are put into the scanner. Slowly, the shape of blooming on the Bourhis screen, like Copepoda Anggun which is not possible-visibility and like shrimp, with hairy antennas to the display.

“You see through a microscope and there are all over the world,” – Plankton Specialist Lionel Guidi

“We have some handsome ones,” he said, grinning.

He began transferring digital images to the database operated by AI which is able to sort Zooplankton based on groups, families, and species.

“They have a complement everywhere,” added Lionel Guidi. “The arm points in all directions.”

One of the deep sea creatures, is called Fronimaeven inspired monsters in the film Ridley Scott 1979 Foreign. “You see through a microscope,” Guidi said, “and there is the whole world.”

Anthéa Bourhis, 28, a lab technician at Villefranche Oceanography Lab, known as LOV, poured morning catch on a scanning machine to produce a digital zooplankton image.

From science to policy

Changed world – and not fast enough to be understood by satellites or snapshots. That is why the long-term LOV series is important: it captures a trend that stretches for years and even a few decades, helping scientists distinguish the natural cycles from changes that are driven by the climate.

“When we explain that if there are no more plankton, there will be no more life in the ocean. And if there is no more life in the ocean, life on land will also not last longer, then suddenly people become much more interested in protecting plankton problems,” said Jean-Olivier Irisson, another plankton specialist in Lov.

Next week, only 15 minutes on the beach, the City of Nice is the host of the third UN Samudra Conference (Unoc3) -CTT five days that unites scientists, diplomats, activists, and business leaders to map courses for sea conservation.

Among the priorities of the meeting: advancing the ’30 30 ‘promise to protect 30 percent of the oceans in 2030 and bring a high sea agreement, or’ BBNJ Accord ‘to protect life in international waters, closer to ratification.

Guidi underlines the urgency of this unable to be led effort, saying: “All of this must be considered with people who are able to make laws, but based on scientific reasoning.”

He did not claim to write his own policy. But he knew where science was suitable. “We convey scientific results; we have evidence of phenomena. This is not an opinion, that’s a fact.”

So, in Villefranche, Lionel Guidi, Anthéa Bourhis and Captain Carval continued their work – transporting lives from the sea, capturing them in pixels, counting their limbs, and sharing their data with scientists around the world. By doing that, they mapped not only the ocean threatened, but the invisible thread that binds the life itself.

JamzNG Latest News, Gist, Entertainment in Nigeria

JamzNG Latest News, Gist, Entertainment in Nigeria